Contemporary age (19th century)

Military heritage

With the defenses consolidated, military engineering focused on the area outside the walls and specifically on the isthmus that joins the city with San Fernando to project defensive systems.

Maritime heritage

The port of Cádiz continued with the same image until the middle of the century, with a small riverside quay attached to the walls and the Capitanía quay protected by the bastion of San Felipe.

Industrial heritage

The main areas of orchards were no longer located within the walled city, since practically all that space was urbanized, so the area outside the walls took over the witness of this economic activity.

The constitutional capital of Spain

The War of Independence (1808-1814) had a decisive effect on Cádiz, since it became the only redoubt that was not occupied by the French and led to the first properly Spanish constitution, the Cádiz Constitution, known as the Pepa, was approved on March 19, 1812 in the city.

It was the response of the Spanish people to the invading intentions of Napoleon Bonaparte. The response of the citizens led to a more radical reform and the Regency convened a meeting of the Cortes on the island of León on September 24, 1810. It combined the traditional laws of the Spanish Monarchy and incorporated principles of democratic liberalism such as national sovereignty and the separation of powers.

The sovereignty, full and supreme power of the State, which until then had corresponded to the King, now passes to the Nation, as a supreme entity and distinct from the individuals that comprise it, represented by the deputies, without estates or imperative mandate. The separation of powers followed the model of the French constitution of 1791 and that of the United States, which prevented the birth of the parliamentary regime in Spain.

It had an ephemeral validity, Fernando VII repealed it on his return to Spain in 1814, implanting absolutism for six years. After Riego’s pronouncement in 1820, the King was forced to swear to the Constitution of 1812, thus beginning the liberal Triennium. With this, the validity of the Cadiz Constitution ended, but not its influence, which weighed on national politics until 1868 and during the rest of the liberal cycle.

During the 19th century, hardly any major works were carried out in the city except for the opening of spaces within the intramural area. The typical farmhouse of Cádiz was formed in the 18th century under the patterns of urban neoclassicism, the influence of a late baroque and the need to raise the buildings to alleviate the lack of space.

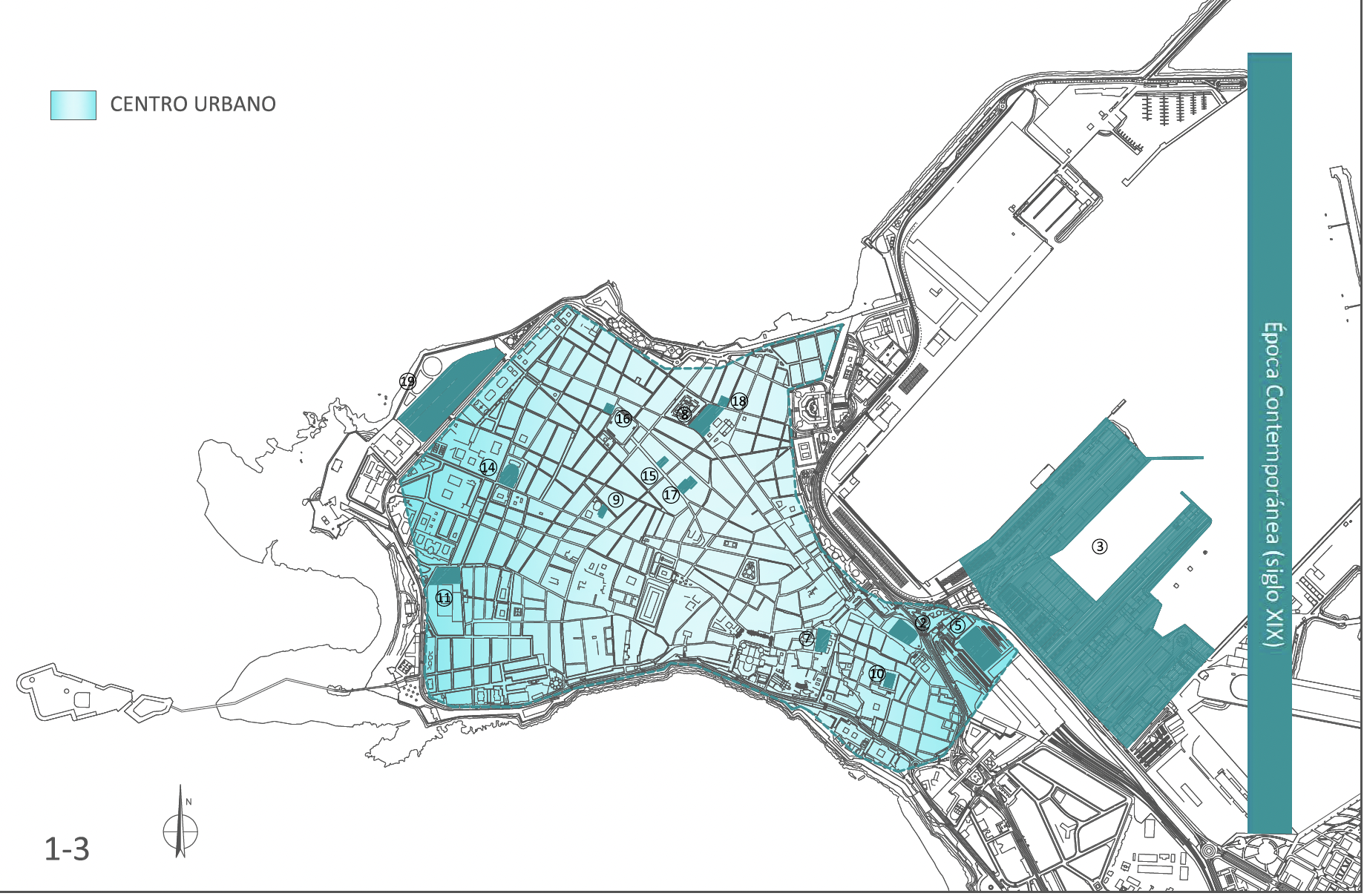

The division of neighborhoods in the 19th century was practically the same since the beginning of the century. The city was divided into 18 intramural neighborhoods that included La Merced and Santa María, San Roque and Boquete, Santiago, Ave María, Nuevo de Santa Cruz, Capuchinos, San Lorenzo, La Viña, Nuevo Mundo, Cruz de la Verdad, Cuna, San Felipe Neri, El Pilar, Angustias and San Carlos, Rosario, Candelaria, San Antonio and Bendición de Dios and the neighborhood of San José outside the walls.

In 1822 an administrative reform was carried out of an urban structure based on barracks and neighborhoods with a parish allocation, subdivided into blocks and houses in an odd order to the right, correlative and independent in each area and managed by the Provincial Councils and by the Councilors of neighborhood. This division led to the creation of 4 barracks and 12 neighborhoods, not including San José: Santa Cruz Barracks, Las Escuelas, Pópulo and Merced neighborhoods; Rosario Barracks, San Carlos, San Francisco and Post Office neighborhoods; San Antonio Barracks, Constitución, Hércules and Cortes neighborhoods; and San Lorenzo Barracks, Barrios de la Palma, Hospice and Libertad.

At a later time, around 1830, a new administrative division was introduced to subdivide the space of the city between the Barracks of the Blessing of God, which included the neighborhoods of San Antonio, Cruz de la Verdad and Nuestra Señora de la Bendición de Dios; the San Carlos Barracks with the neighborhood of Nuestra Señora del Pilar, Nuestra Señora de las Angustias, San Carlos, Nuestra Señora del Rosario, de la Cuna and San Felipe; the San Lorenzo Barracks that included the Barrio del Nuevo Mundo and San Lorenzo; the Cuartel de la Candelaria with the neighborhoods of Candelaria, Santiago and Ave María; and the Santa María Barracks with San Roque and Boquete and Santa María and La Merced.

Starting in 1849, the neighborhood of San Carlos was unified with that of San Francisco and in 1869 the neighborhood outside the walls of San José came to be considered as a district of the city. The last reforms at the end of the century concern the subdivision of some neighborhoods such as La Merced, Santa María, Hospicio, El Balón, La Palma, San Lorenzo, San José and San Severiano.

The height of the buildings was the subject of continuous surveillance by the authorities who, since the 18th century, imposed the norm of limiting the height to 20 yards, not including the lookout towers, when a new building was projected.

In addition, there was also an impact on the construction of a water collection system that from the pipes that came from the roofs communicated directly with the cisterns that served to supply the neighborhood with water.

The buildings were built in oyster stone in most cases, completed by masonry, wood for the ceilings and wrought iron for the exterior openings. The houses that belonged to the commercial bourgeoisie were completed with a decoration based on marble, plaster and paintings both on the exterior faces of the buildings and in the internal rooms.

In this stage, three types of houses were built: the one known as “main” under the commercial bourgeois pattern that brought together in its space the dependencies destined for the warehouse on the ground floors, the offices on the first floors, the dwelling on the upper floors. and those of the service that occupied the highest floors without counting the lookout tower; the other type of dwelling was called “the one with bodies” in which the floors were not differentiated but the dwellings were independent; and lastly, the tenement houses that were built for the lower classes of the city with much smaller divisions that on some occasions resulted from a subdivision of an older building.

However, in the middle of the 19th century, a novel, very ornamental decorative style was generated, according to the tastes of the bourgeoisie, which is called “Elizabethan” because it coincides chronologically with the stage of influence of the reign of Elizabeth II.

Among the most outstanding urban interventions of this century in Cádiz, the culmination of the dome and the sacristy of the Cathedral, the Public Market of the Plaza de la Libertad, the reform of the Plaza de Espoz y Mina and the Academy of Fine Arts (Callejón del Tinte) for the disentailment of the Franciscan Convent and the Bullring by Juan Daura. On the other hand, the Arco del Pópulo was reformed, the Town Hall was enlarged, the Teatro Circo Gaditano was built, the Gran Teatro was built -later Gran Teatro Falla- and again a Bullring was erected due to a collapse under the orders of Garcia del Alamo.

To these urban works must be added the Paseo de la Alameda de Manuel Bayo, the extensions of the Plaza del Mentidero and the Plaza de la Catedral, the cobbled, paved and paved streets and sidewalks, the Parque Genovés and the construction of a ring road through the intramural area.

It should be noted that the headquarters of the Municipal Center of Flamenco Art “La Merced” used plans from 1895 by the architect Eiffel originally designed for the structure of the old Genovés Park Theater, in order to modernize the aesthetics with iron architecture.

Evolution of the city of Cádiz through its military, maritime and industrial heritage (MMI)